A Decisive Moment for Modernism

The encounter of Johannes Itten and Joseph Matthias Hauer at the gallery of the Freie Bewegung in Vienna

By Dieter Bogner

In the spring of 1919, an encounter than can be described as a great moment for 20th century modernism took place between an Austrian composer, Joseph Matthias Hauer (1883−1959), and the Swiss painter Johannes Itten (1888−1967) in the exhibition space of the artist group Freie Bewegung in Vienna’s Kärtnerstraße. The following article reconstructs the unfolding of the event and sketches its music-historical consequences.

In 1917, Johannes Itten had moved from Stuttgart to Vienna to found a private art school there. Already in summer 1919, he left Vienna again for Weimar, following a call from Martin Gropius to teach at the Bauhaus. In a letter from 1962, he wrote down his memories of the unfolding of events: Joseph Maria Hauer, he writes, “…kam nach oben (es war am Tage vor der Eröffnung) trat ein und ging von Bild zu Bild und stellte sich mir vor schliesslich und sagte–‘Ich bin Komponist und habe in meiner Tasche Briefe an meine Freunde um ihnen mitzuteilen dass ich derart hoffnungslos in die Zukunft sehe, dass ich mich entschlossen habe nie mehr eine einzige Kompos. mehr zu schreiben; seit ich jetzt hier ihre Bilder sah verspreche ich Ihnen, dass ich diese Briefe verbrenne und mit neuer Hoffnung an die Arbeit gehe‘.”1

What had happened? In the years before the encounter, Joseph Matthias Hauer experiences a deep creative and identity crisis, which manifests itself in the fact that ever since the creation of Opus 12 in 1915, he does not finish a single composition. Instead of composing, he intensively engages himself in questions of musical theory. For a few weeks in January and February 1919, he writes letters addressed to friends and supporters on a daily basis.2 His theoretical considerations revolve around the question of how, after the dissolution of the traditional musical order by Arnold Schönberg, the creation of great musical forms could still at all be possible. In one of the letters, his desperation manifests itself particularly drastically: He fears to have reached the limit of the capability of musical articulation and, through that, to eventually end up in “Geräuschlosigkeit, Unsinnlichkeit“ and thus in a complete “Vergeistigung“ and “Musikdenken (ohne Spielen, Aufführen, Lärmen)“, because, as he continues, “das Chaos, dessen Überwindung mein Lebenswerk war, ist durch die Temperatur zum ‚Nichts‘ organisiert und die ‚Musik‘, die ich mein Leben lang immer hoffte, wächst immer mehr ins Schweigen, ins Denken, in die Ruhe hinein“.3

The long lasting struggle for new principles of form ends abruptly in the first days of May 1919. The writing down of Opus 15 takes place between the 30th of April and 4th of May.4 Within the same month, he produces Opus 16, followed by Opus 17 and 18 in July/August. During the last days of August, Hauer writes Opus 19; the, seen from a music-historical perspective, revolutionary foundingpiece of the Viennese twelve-tone method—notably several years before Arnold Schönberg develops and publishes his first twelve-tone compositions based on his own methodology.5 In the following years, he continues to work on the further compositional and theoretical formulation of the “twelve-tone method” with great intensity.6

One could interpret Itten’s decade-old memories about the decisive encounter with Joseph Matthias Hauer as idealised representation, were it not for an eye- and ear-witness of the discussion between composer and painter. Ferdinand Ebner, philosopher, friend and important interlocutor of Hauer’s, notes in his diary on the 7th of May: “Der Hauer schleppte mich in die Ausstellung des Schweizer Malers Johannes Itten. Das ‘Schöpferische‘ im Auge musiziert in Farben und geometrischen Formen: mein Verstand begreift mehr als meine Psyche ästhetisch ergreift. Die Geburt des Ohrenmenschen in Europa. Die Geburt von Farben und Formen aus dem Geist der Musik. Das Ende des Idealismus. Der Hauer fing mit dem Itten ein Gespräch über die Klangfarbe an. Ich verließ ihn und rannte auf dem Graben einige Male hin und her. Wohin gerate ich innerlich? Nach dem Abendessen spielte der Hauer seine letzten Kompositionen. Kühles Raisonnement, Klangfarbenästhetizismus. Ich werde noch am Wortloswerden meiner inneren Existenz geistig ersticke –“.7 The described composition could be Opus 15, completed just a few days earlier.

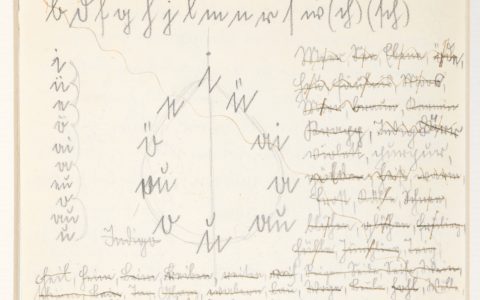

In a following report, Ebner describes the extensive concordance in the artistic strivings of both the composer and the painter found in each other’s œuvre: “Es ist kein Zufall“, he writes, “daß zwei Menschen, ein Komponist und ein Maler, Josef Hauer und Johannes Itten, gleich vom ersten Augenblick ihrer Begegnung an, auf die ersten miteinander gewechselten Worte hin, und das erste gegenseitige Bekanntwerden mit ihren Werken, sich so in wechselseitigem Verständnisse trafen, daß der Maler sagen konnte, was ihm Hauer auf dem Klavier vorspiele, seien seine eigenen (des Malers) Kompositionen, die er komponiert hätte, wenn er eben nicht Maler, sondern Musiker wäre; wie ja auch Hauer von den Gemälden Ittens behauptet, sie erfüllten alles, was er sich von Bildern und der Kunst des Malens im besonderen seit jeher erwartet und gewünscht habe. Ja, so weit geht sogar dieses gegenseitige, in seiner Unmittelbarkeit gewiß wunderbar anmutende Verständnis, daß Hauer ohne weiteres geneigt ist, sein für sein ganzes musikalisches Schaffen am meisten charakteristisches Werk–und das ist eben die Apokalyptische Phantasie–mit der größten und bedeutendsten Schöpfung Ittens (das diesem Aufsatz beigelegte Bild) zu identifizieren; wozu Itten ganz und gar seine Zustimmung gibt. Jedenfalls hat das Schaffen beider eine gemeinsame ‘innere‘ Voraussetzung in der angenommenen tiefer im ‘Subjekt‘ wurzelnde Identität des Seh- und Hörakts.”8

With regard to content, the question of congruence between painting and music, between colour and tones, stood at the centre of the discussions between Itten and Hauer. One of the painter’s principal works, Aufstieg und Ruhepunkt, created in Vienna in 1919, can be considered, according to his stage of development at that time, as Itten’s completed expression of his observations regarding his theory of art and colour.

Hauer must have experienced a “productive shock” when faced with Itten’s compositions. It abruptly broke his yearlong artistic blockade, led to the spontaneous resumption of his compositional activity and a few months later, to the long yearned for goal of overcoming “Schönberg’s chaos”9 through the discovery of the “twelve-tone law”.

Only very rarely is it possible to set a precise date, almost to the exact day, of a decisive moment of Modernism and to reconstruct it in such lifelike detail with the help of the authentic foundation of reports of eye- and ear-witnesses. The creative impulses that the encounter of Joseph Matthias Hauer and Johannes Itten in the exhibition galleries of the artist group Freie Bewegung had on the work of both artists, render the exhibition of the Swiss painter one of the most significant in matter of historical influence, and thus one of the most important exhibitions generally, that took place in Vienna.10